Benin – Multiplying militancy

- The Islamic State (IS) claimed on 16 September its inaugural acts of violence in Benin.

- In doing so, IS joins the more developed and sophisticated al-Qaeda-affiliated JNIM extremist group, which is principally operating out of Benin’s Atakora department.

- With both groups solidifying what was a transitory presence in Benin, the government of president Patrice Talon has galvanised international support for the country’s counterterrorism response.

- While this will ultimately enhance the capabilities of state-aligned forces, it does risk internationalising the country’s counterinsurgency response, which could provide further impetus for terrorist attacks in Benin.

In its weekly al-Naba publication published on 16 September, the Islamic State (IS) transnational extremist network claimed its inaugural acts of violence in Benin. In al-Naba, IS stated that members of its Sahelian affiliate, the Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS), had killed four soldiers on 01 July in the Alibori department town of Alfa Kawoura. The claim in question does not corroborate with any reported act of violence in the region. The extremist organisation also laid claim to an incursion that occurred a day later in the W National Park, which spans across the tri-border area between Burkina Faso, Niger and Benin’s Alibori department. Here, the extremist group claimed that members of its ISGS network ambushed and killed two Beninese soldiers – providing photographic evidence.

Transitory terrorists

While indeed marking the first acts of violence to be formally claimed by ISGS in Benin, the presence of the IS affiliate is by no means novel. Reports from as early as June 2020 referenced a suspected ISGS cell operating in Alibori between the borders of Benin and Niger. Citing eyewitness accounts, the reports noted that the ISGS cell identifies itself as katiba Usman dan Fodio – a reference to the founder of the antiquated Sokoto Caliphate – and is believed to be led by a Beninese national identifying himself as Abdallah.

Little is known about the ISGS commander apart from reports that he is a veteran of the Malian war (2012/13), in which he fought on behalf of the Movement for Oneness and Jihad (MUJAO) – a militant outfit that was the predecessor to ISGS. Katiba Usman dan Fodio’s presence in Benin was initially thought to be transitory, with the militant group using Beninese territory as a fallback zone during counterterrorism operations targeting its positions in south-eastern Burkina Faso and south-western Niger.

However, after first being spotted in the W Park area in June 2020, the ISGS faction is said to have engaged in acts of radicalisation, recruitment, and efforts to reportedly impose taxes on the local population elsewhere in the Alibori department. Specifically, the militant group is said to have been spotted at various times in the district of Karimama, most notably in the localities of Gorouberi, Mamassi-Fulah, Karimama centre, Bogo-Bogo, Garbeye-Koara and Kompanti. In the neighbouring district of Malanville, katiba Usman Dan Fodio was said to have been seen in the locality of Wollo Chateau.

The assailants of Atakora

The situation is said to be worryingly similar in Alibori’s neighbouring Atakora department. A key difference, however, is that Atakora hosts a perceivably more sophisticated militant presence. The Atakora department has emerged as a key operational zone for the al-Qaeda-aligned Jama’at Nusrat ul-Islam wal-Muslimeen (JNIM) movement that has either claimed – or is believed to be responsible for – more than a dozen attacks in Beninese territory since 2019. Indeed, from seemingly established operational bases in Burkina Faso’s Est region (which borders Atakora department), JNIM has made a number of incursions into the administrative division for varying purposes. These attacks have escalated since first being reported in 2019.

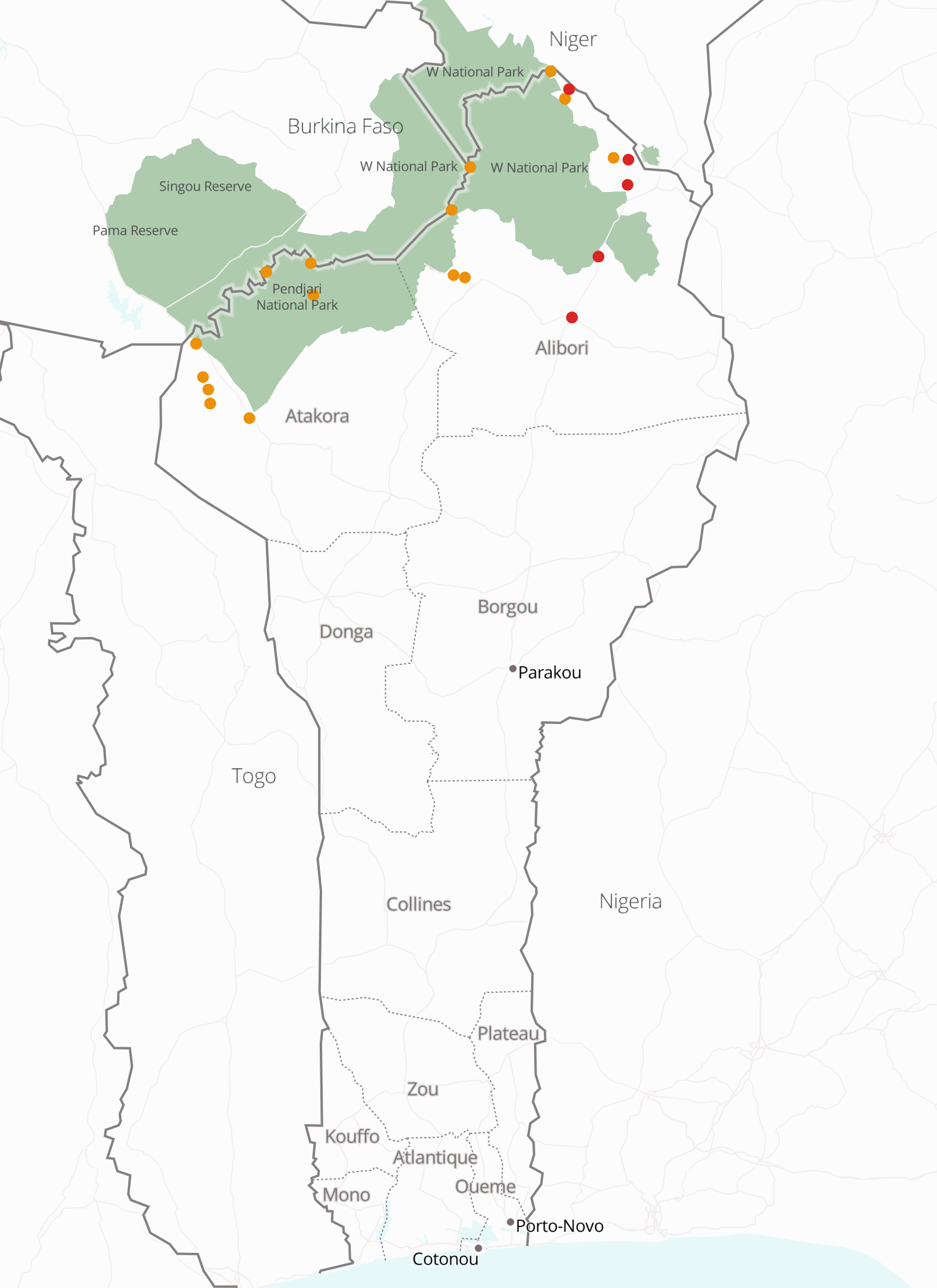

Confirmed and suspected attacks by JNIM (orange) and ISGS (red) in Benin between 01 September 2019 and 28 September 2022

[Data Source: ACLED Map: MapBox]

Initially, it appeared that JNIM’s presence in Atakora was largely transitory or a means for the group to benefit from the illegal trade of ivory, artisanal gold, and arms that occurs within the densely forested area between Burkina Faso and Benin. However, as JNIM’s position within Burkina Faso’s Est region strengthened since around 2019, it appears that the group has expanded an operational presence to Beninese territory.

This as much was postulated by researchers at the Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael Institute). In a July 2021 report based on extensive fieldwork and interviews, Clingendael researchers claimed that JNIM had established three primary bases along the Burkinabe side of the Burkina Faso-Benin border, namely in the Pama Reserve, the Singou Reserve, and within the W National Park near the Est region commune of Tapoa-Djerma.

From these camps – which reportedly host as many as 300 JNIM fighters – insurgents have shifted from using Benin as a resting point and are instead exploiting the Atakora department, particularly localities along the Porga-Tanguieta-Natitingou highway, for supplies to fuel its insurgency across the border in Burkina Faso.

Recalibrating the rangers

The government of president Patrice Talon has responded proactively to the growing extremist contagion. From a domestic perspective, Benin has changed a conservation force into a specialised counterterrorism unit.

Since around mid-2020 when extremist violence in Benin begun escalating, African Parks has been mandated by the Talon administration to include counterterrorism and counter-insurgency activities within the scope of its operations, which was initially limited to conservation and anti-poaching initiatives. In total, African Parks has deployed more than 300 armed members to the border areas such as the Pendjari National Park and W National Park, where they are equipped with military grade weapons and a fleet of drones to assist their surveillance capabilities. Unconfirmed reports claim that African Parks is also getting significant operational and logistical support from a number of undisclosed Western governments of late.

Foreign friends

Indeed, Benin’s counter-terrorism response – which to date has served to limit the scale of extremist violence in comparison to neighbouring Niger and Burkina Faso – is drawing further regional and international support.

For example, Chinese ambassador to Benin, Peng Jingtao, declared his country’s desire to support Benin in its fight against violent extremist and terrorist activities during a 10 August interview with local media. In this regard, Peng stated that China is willing to strengthen its military cooperation with Benin. In addition, French president Emmanuel Macron stated during his 27 July visit to Benin that France would also assist the West African state in its anti-terrorism efforts. On 06 July, the United States donated USD 15 million to Benin to strengthen its security sector.

More recently, government spokesperson Wilfried Leandre Houngbedji confirmed on 10 September that the Beninese government has been in talks with Rwanda to sign a military agreement. According to Houngbedji, the convention would see Rwanda provide logistical support and train Beninese soldiers to fight against violent extremist activities. Houngbedji revealed that the agreement would not entail Rwandan soldiers being sent to Benin.

The Signal

Benin is not assessed as having any homegrown extremist groups, but instead faces a threat of spill over from militant entities that maintain an operational presence in its border areas with Burkina Faso and Niger. That said, there is a possibility of extremist groups co-opting local populations into joining their respective organisations – and thereby developing an organic homegrown insurgency. Factors that could influence such an outcome will be the conventionality of the state’s counterterrorism response, the prevalence of socio-economic grievances among local populations, and the occurrence of communal tensions that extremist groups have demonstrated a capacity to harness to their advantage. In the case of Benin, all of these factors are currently present, albeit to a lesser degree than neighbouring countries, rendering the country at a low-to-moderate risk of homegrown extremism.

The operationalisation of ISGS militants in Benin suggests that the group may be seeking to encroach and hold territory. Like other Islamic State (IS) affiliates, the primary objective of ISGS is to seize territory that it can govern under the IS banner and according to the tenets of Sharia law. In attacking government forces in Benin, ISGS may no longer want to establish itself as a merely transitory force using Beninese territory as a fallback zone from its key operational theatres in neighbouring Burkina Faso and Niger. Instead, the group may be using violence as a means of discrediting and destabilising the authority of the state. There is little evidence to suggest that the group has the capacity at this stage to fully displace security and governance structures and impose its governance system on population centres. Nonetheless, it is anticipated that the group will increase the frequency, and possibly the scope, of its attacks in the Alibori department, particularly in and around the W National Park, which remains difficult to secure.

The confirmation of ISGS operations in northern Benin could also lead to an uptick in violence by JNIM. In jurisdictions where ISGS and JNIM are both present, the groups have competed for resources, recruitment, and control of key smuggling routes, often violently so. In the so-called Gourma zone of Mali for example, ISGS and JNIM directly engaged in violent clashes between 2020 and 2021 that involved significant losses for both organisations. This eventually led to a halt in direct confrontations, with each favouring using violence against state-aligned and civilian interests as a means of asserting relative superiority. In this regard, the arrival of ISGS in Benin could prompt JNIM to demonstrate its dominance through the intensification of violence within its areas of operation in northern Benin. This is most likely to play out through acts of violence in the Atakora department, particularly in and around the Pendjari National Park and along the Porga-Tanguieta-Natitingou axis. Acts of violence by JNIM are expected to mostly discriminate against security interests, with the group likely to specifically target members of African Parks due to its spearheading of counterterrorism operations in the region. In turn, ISGS is also likely to attempt to increase the frequency and intensity of its attacks in Alibori department, particularly in the communes of Karimama and Malanville. Although similarly expected to target state-aligned interests, violence by ISGS may also target civilian settlements that are deemed to be cooperating with African Parks and related counterterrorism structures. Other sites that could equally be targeted by ISGS include churches, schools, and the field offices of non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

There are several factors that may motivate either ISGS or JNIM to attempt a mass casualty attack in major cities such as Cotonou, Porto-Novo or Parakou. For one, the efficacy of the counterterrorism prowess of African Parks may prompt militant groups to seek softer targets as a means of demonstrating relative strength. Both JNIM and ISGS have leveraged off mass casualty attacks in populated centres as a key propaganda tool to demonstrate strength and relevance. Anecdotal evidence suggests that both groups may be particularly prone to such acts of violence during periods of sustained counterterrorism operations against their positions – a scenario that is possible amid the mobilisation with African Parks and its stated intention to better coordinate security initiatives with neighbouring states such as Burkina Faso and Niger. Benin’s diplomatic alignments with France, the United States and China could also serve as the impetus for militants to target a major urban centre. This is usually due to major urban locales hosting facilities of commercial and/or diplomatic interests that are often symbolic of the state’s political alignment with the international community. This includes – but is not limited to – foreign embassies, Western-branded hotels and commercial chains, government offices, and security installations.

That said, the ability of groups such as JNIM and ISGS to undertake a complex attack in a Beninese urban centre is considered limited at this stage. This is due to the lack of an established operational network that either group possesses outside of Benin’s Atakora and Alibori departments, which complicates attempts to plan and execute a successful attack in a major urban centre. Moreover, growing cooperation between Beninese and Western security agencies should provide the West African country with intelligence that could assist in pre-empting any coordinated acts of violence in the country. While an attack against a key political or economic centre in Benin cannot be entirely discounted, any such acts of violence are likely to be opportunistic and therefore limited in overall violence and disruption.