Burkina Faso – Step by step

- The ECOWAS regional bloc has approved the interim government’s 24-month timeline to return the country to civilian rule.

- The bloc’s approval of the timeline grants the interim administration much-needed political capital and international legitimacy.

- This could facilitate a gradual resumption of donor support, enhancing the country’s medium-term economic prospects.

- However, persistent insecurity – and the country’s vulnerability to the externalities of the Ukraine conflict – present modest headwinds to an otherwise stable outlook.

On 03 July, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) approved the interim government of president Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba’s revised timeline of 24 months to return Burkina Faso to constitutional rule starting from 01 July.

Slow compromise

Damiba had initially ratified a transitional charter of 36 months on 01 March. However, this was rejected by ECOWAS on 25 March after the bloc had called for a timeline of no longer than 12 months. The regional bloc subsequently gave the interim government until 25 April to produce an “acceptable plan for a transition”, failing which undisclosed financial and economic sanctions would be imposed. ECOWAS also demanded the immediate release of ousted former president Roch Marc Christian Kabore, who was in state custody at the time.

While Kabore was subsequently released on 07 April, the interim government sent a request to ECOWAS on 22 April for additional time to formulate a new transition timeline. ECOWAS did not publicly respond, but this request was seemingly the reason why sanctions were not imposed against Burkina Faso when the 25 April deadline expired.

Nonetheless, with no new roadmap and the threat of sanctions still looming ahead of ECOWAS’s 04 June summit, the Damiba administration sent another communique to the regional bloc on 31 May. In the notice, the interim government expressed its commitment to continue dialogue with the regional bloc to ensure a return to constitutional order as soon as possible. During the 04 June summit, ECOWAS welcomed the communique and the release of Kabore and confirmed that it would engage in dialogue with transitional authorities to reach a mutually agreeable timetable.

ECOWAS appointed former president of Niger, Mahamadou Issoufou, as its envoy to spearhead discussions with Burkinabe authorities as a means to achieve this objective. Associated negotiations that commenced in June culminated with the interim administration proposing the new 24-month timetable on 01 July, as well as suggesting the development of a monitoring and evaluation mechanism to ensure that the transitional roadmap is adhered to. During the 03 July summit, ECOWAS lauded the proposed creation of an oversight mechanism and deemed the new transitional roadmap acceptable. As a result, the regional bloc formally withdrew its threat of sanctions against Burkina Faso; however, it maintained the country’s membership suspension from the regional bloc that had been imposed in the aftermath of the January coup.

Danger zone(s)

While the Damiba administration immediately welcomed the decision to lift the threat of sanctions, it also called on ECOWAS to provide sufficient – unspecified – support to Burkina Faso’s transition and the core processes underpinning it. Chief among these is addressing a rapidly expanding Islamist extremist insurgency.

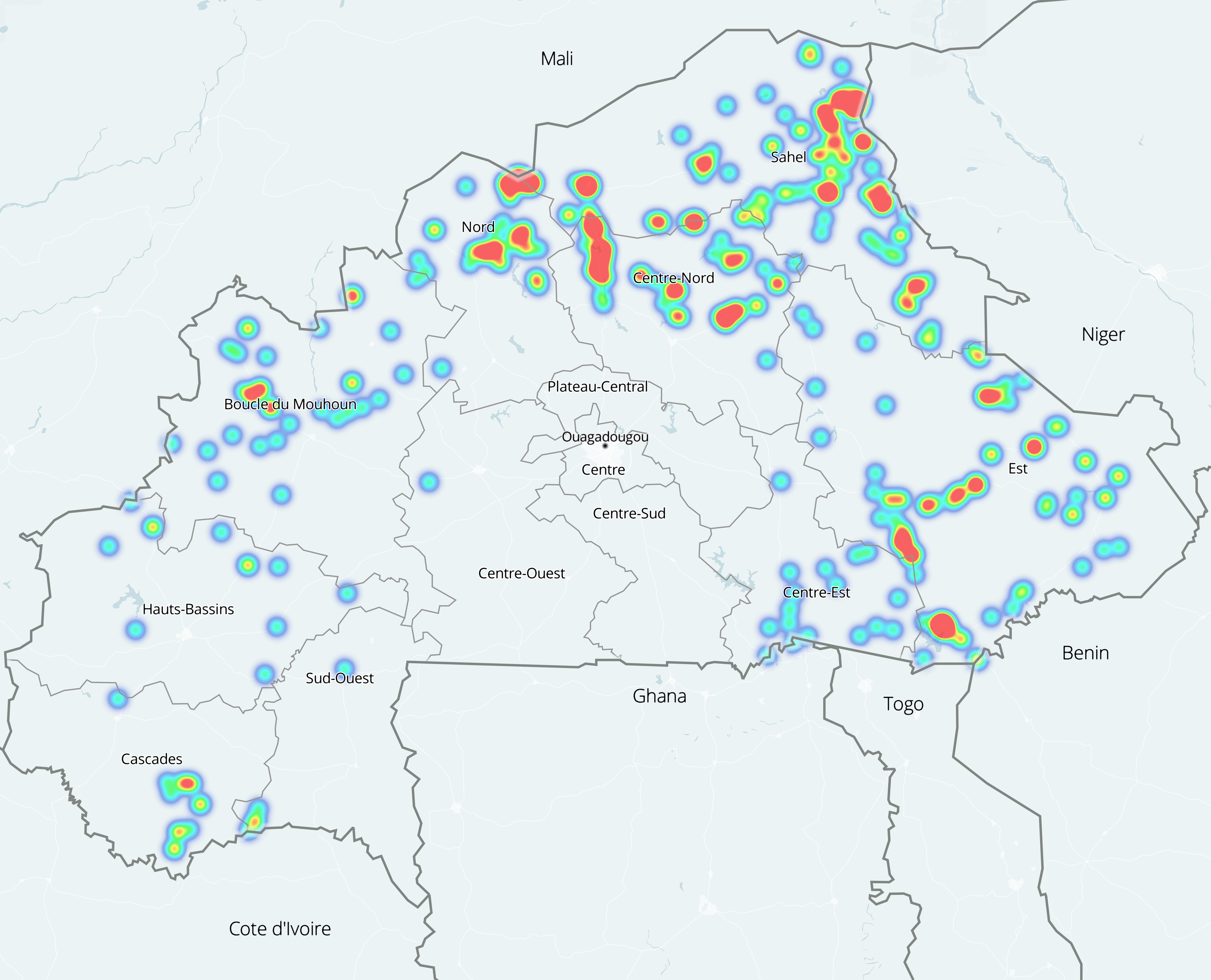

The persistence of extremist violence was Damiba’s primary justification for spearheading the January coup, but the military takeover has had little impact on Burkina Faso’s security environment to date. In fact, insecurity has ostensibly worsened. As per the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, a total of 456 militant attacks were recorded between 01 September 2021 and 01 February 2022. In comparison, 504 militant incursions took place between 02 February and 01 July. The number of mass-fatality attacks – in which ten or more people were killed – also increased after the coup, with 27 such incidents recorded following the putsch, compared to 17 in the preceding five-month period. The most notable of these occurred on 11 June, when over 100 people were killed during an attack by members of the Islamic State-affiliated ISGS group in the Seno province commune of Seytenga (Sahel region).

[Geographic distribution of militant violence from 01 February to 01 July]

[Data Source: ACLED Map: MapBox]

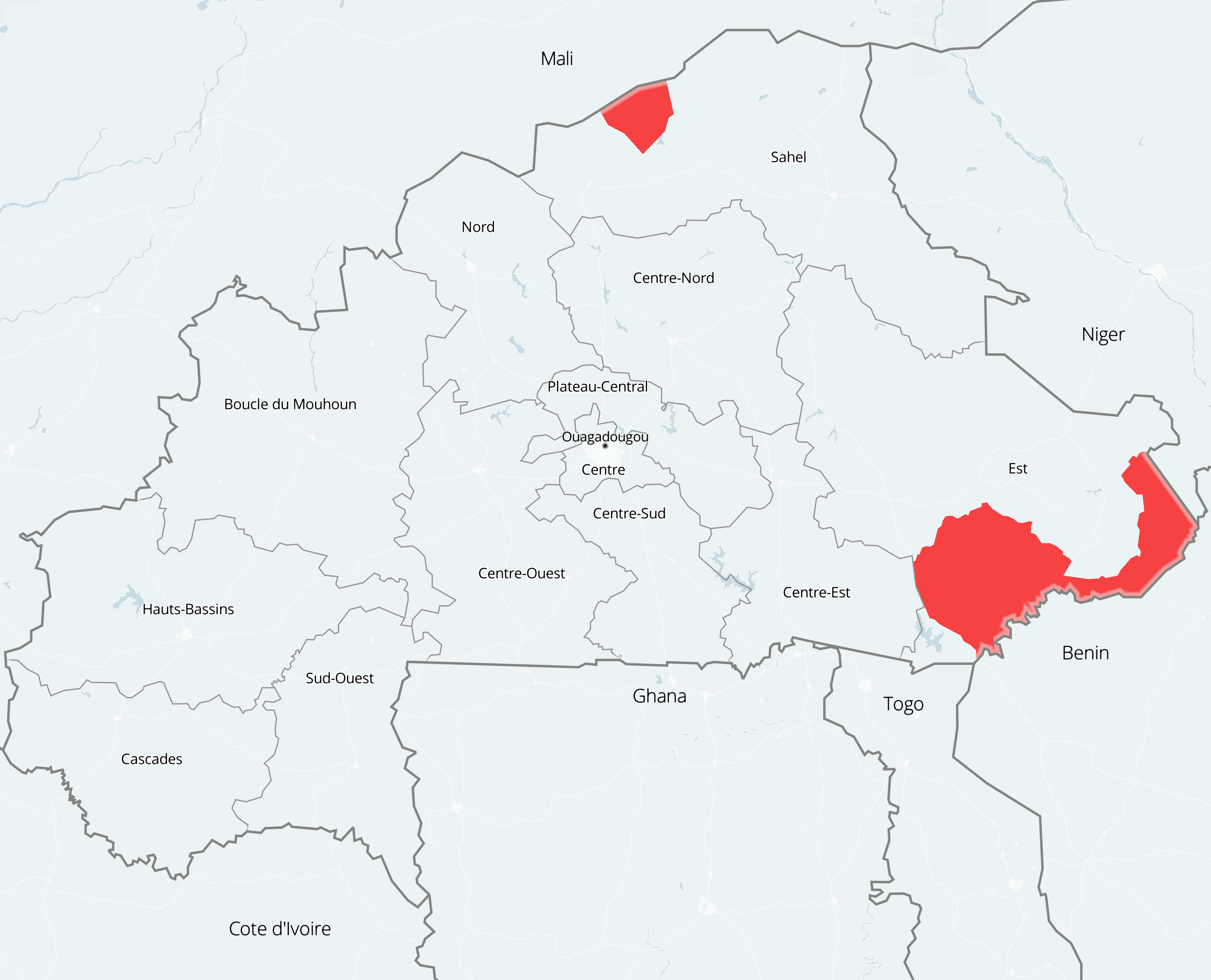

Following several months of military operations that generally mirrored those under the former administration, the government took a decisive step on 20 June, when the High Council for National Defence announced the establishment of special military zones in the Est and Sahel regions.

In Est region, the military zone will encompass the forested areas of Arly-Singou, Koutiagou, and W National Park, all of which straddle the border with Benin, and are where the al-Qaeda-aligned JNIM movement has a pronounced presence. The second military zone will be established within a portion of the Sahel reserve situated in the province of Soum (Sahel region), which shares a frontier with Mali and is where ISGS is particularly active.

The primary feature of these zones is that civilians are prohibited from entry. In this respect, those residing within the zones were on 24 June given 14 days to vacate to designated areas in neighbouring localities. The Est region area is generally unpopulated, while the Sahel reserve has a handful of small towns. While local reports indicated that the government has facilitated evacuation efforts, it remains unclear at the time of writing whether such operations formally concluded by the 11 July deadline, or when military offensives within these zones will commence. It is perceived though that the military will ensure that all civilians are evacuated before beginning the operation.

[Military zones highlighted in red]

Budgeting

With Damiba’s pre-occupation with militant violence, it is unsurprising that security spending will take up roughly 50 percent of expenditure earmarked for transition-related expenses.

This much was disclosed when finance minister Seglaro Abel Some presented the Medium-term Budgetary Framework on 30 June. In his presentation, Some revisited the amended 2022 budget, which the transitional government adopted in March after making adjustments to the fiscus passed by the Kabore government in December.

The pillars

The total envelope amounts to XOF 2.91 trillion (USD 4.445 billion), of which roughly XOF 2 trillion will be financed from domestic revenue and XOF 300 billion from donations. The remainder is expected to come in the form of loans. Of total expenditure, XOF 504 billion has been allocated to what the government refers to as the three “pillars” of the transition. Pillar one (“fighting terrorism and restoring the integrity of the state”) is geared towards enhancing the capabilities of the country’s security forces to more effectively curtail militant violence and has been allocated XOF 280 billion. Pillar two (“response to the humanitarian crisis”) is aimed at addressing the socio-economic impact of insecurity and has been allocated XOF 98.6 billion. Pillar three (“refounding the state and improving governance”) relates to strengthening the capacity of government institutions and has been allocated XOF 136.4 billion.

Outlook

The budget envisages a GDP growth rate of 6.6 percent in 2022, compared to 6.9 percent registered in 2021 (and 1.9 percent in 2020). Growth for 2022 is expected to be driven by the country’s key agricultural and mining sectors. The fiscal deficit is projected to narrow from 5.6 percent of GDP in 2021 to 4.9 percent in 2022. This reflects projections of marginally higher revenue from the agricultural sector, consolidation of personnel expenditure and the initiation of tax policy and revenue administration reforms, balanced against higher security and social spending.

Pressure

Projections in the budget may yet be altered given a worsening external environment due to the Ukraine conflict and associated uptick in global fuel and food costs. In this respect, Burkina Faso has been particularly affected given that it imports 55 percent of its wheat from Russia and another 5 percent from Ukraine. This has seen an uptick in imported food costs. At the same time, an escalation in global fertiliser prices associated with the conflict has resulted in a price hike for domestically grown produce. As a result, year-on-year inflation reached a 24-year high in May at 15.3 percent, more than double the 7.2 percent registered in January.

In response, the government has undertaken several measures to soften the impact of these exogenous pressures on domestic prices and industries. In the key cotton sector for example, the government unveiled in May a XOF 72.2 billion subsidy to reduce the costs of fertiliser and pesticides for farmers. Then, on 30 June, the Ministry of Industrial Development, Trade, Handicrafts, and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises issued a statement indicating that it has established a fixed price for staple foods (the duration of the price cap was not revealed). The government has also continued to engage with local suppliers and farmers as a means to possibly develop additional solutions.

The Signal

The administration of interim president Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba is expected to adhere to the new 24-month transitional roadmap. Since the onset of Burkina Faso’s transition, the Damiba government has been generally cordial with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), demonstrating its receptiveness to the regional bloc’s input (and its responsiveness to the bloc’s threats). As such, ECOWAS – through its envoy, Mahamadou Issoufou – is expected to play an active role in the progression of Burkina Faso’s transition, scheduled to conclude upon the holding of elections in 2024. While this will manifest in continued engagement with local authorities, the regional bloc is also anticipated to form part of the government’s touted oversight mechanism, which should contribute positively to the state meeting its transitional objectives. This should be aided by the generally technocratic nature of the interim government. Moreover, the diverse and inclusive nature of the transitional administration should mitigate any notable pushback to the wider agenda by both political and civic actors. Holistically, the interim administration is not expected to deviate from the new roadmap, at least not without input and approval from ECOWAS. This is due to both the threat of sanctions and the fact that the regional bloc’s approval of the transition is deemed critical to the Damiba government’s legitimacy abroad.

Indeed, Damiba will need to ensure his government has legitimacy among external stakeholders due to economic considerations. While developmental support from the likes of the World Bank and African Development Bank has remained uninterrupted since the coup, significant amounts of bilateral aid have been suspended by key partners such as the United States (US). The US announced in February that it was withholding USD 158 million in development aid to Burkina Faso due to the coup d’etat. This followed a separate decision made by the US shortly after the coup to halt activity related to an agreement signed in August 2020 for a further USD 450 million in funding over a five-year period. Following the 03 July ECOWAS summit, the US government issued a statement that it welcomed the progress made by Burkina Faso and would continue to monitor the transition. Accordingly, as transitional processes move forward, the US may be amenable to resuming, at least partially, its aid support. Similarly, the overthrow of the Roch Marc Christian Kabore administration coincided with negotiations between his government and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, United Nations Development Programme, and the European Union. The consultations were aimed at securing financial support for Burkina Faso’s national economic and social development plan (PNDES-II). The Burkinabe state requires approximately USD 8.12 billion in external funding to finance the first stages of the initiative – measured at an overall cost of USD 29 billion between 2021 and 2025. Negotiations that were subsequently suspended following the coup may yet resume over the near term following ECOWAS’s approval of the new timeline. Finally, the government has indicated as recently as 07 July that it will approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the near term over a potential financing arrangement, the prospects of which would be dependent on the legitimacy and stability of the transitional administration.

Resumption of external aid support would be a boost for Burkina Faso’s medium-term economic prospects. Additional costs associated with food subsidies and a higher import bill are expected to weigh on the country’s internal balances, and will likely result in the government failing to meet its fiscal deficit target of 4.9 percent of GDP in 2022 (compared to 5.6 percent in 2021). However, the resumption of aid would provide the government sufficient fiscal space to sustain current price intervention measures while stabilising internal balances. This will remain critical to the transitional government achieving its medium-term fiscal goals (with a budget deficit of 4.8 percent of GDP forecast for 2023) particularly as military expenditure increases. Indeed, the state envisages an additional 20 percent increase in military spending in 2023.

Inability to meet its fiscal targets may see the transitional government increasingly turn to regional borrowing beyond current projections. As per ratings firm Standard & Poor’s (S&P) in May, the government is expected to meet its growing security funding needs through bond issuances on the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA), which is characterised by higher borrowing costs and shorter maturities. Nonetheless, the IMF indicated in a March report that it does not expect the uptake in loans on the regional market to be excessive, and that total debt-to-GDP will increase from 48.2 percent in 2021 to 48.9 percent in 2022, before reaching 49.2 percent in 2023. Higher interest rates associated with the regional bond issuances are nonetheless anticipated to see Burkina Faso’s debt-service-to-revenue ratio increase from 8.8 percent in 2021 to 9.9 percent in 2022, and then 10.6 percent in 2023 (largely in line with government forecasts). Should the aforementioned international support not materialise – or be less than expected – the government is expected to rely more heavily on regional markets to meet additional expenditure associated with sustained or potentially higher spending on security and subsidies. This would see both debt and associated servicing costs increase over the medium term. However, Burkina Faso’s membership of the UEMOA (and the availability of 5.4 months of import cover as of March) provides the country with sufficient buffers to offset potential balance-of-payments shocks and external volatility, thereby lowering refinancing risks.

Endogenous and exogenous factors will weigh on what is otherwise anticipated to be stable and modest growth over the near-to-medium term. The government envisages a GDP growth rate of 6.6 percent in 2022 and 6.8 percent in 2023; however, these projections are more optimistic than those of the IMF, which has forecast growth of 5.6 percent for 2022 and 5.3 percent in 2023. While the IMF did not provide a rationale for its outlook, it is perceived that the institution factored in the country’s uncertain political context at the time of the assessment in March, resulting in the divergence. Regardless, Burkina Faso’s growth will be driven primarily by the agricultural (in particular, cotton) and mining sectors, all of which have remained largely unaffected by the coup. As for the cotton industry – which accounts for 8 percent of GDP and up to 60 percent of export earnings – the United States Department of Agriculture indicated on 19 May that the 2021-2022 cotton season (August to July) in Burkina Faso is expected to see growth of 7 percent. Meanwhile, the country’s three largest cotton producers, Societe Burkinabe des Fibres Textiles, Faso Coton, and Societe Cotonniere du Gourma, have projected that the 2022-2023 season could see growth of 9 percent due to the government’s subsidy scheme and adoption of new so-called farm gate incentives. Elsewhere, the Burkinabe mining sector (accounting for around 12 percent of GDP) is expected to continue benefitting from an ongoing commodity price rally. Finally, the state has indicated that it anticipates a continuation in the uptick of domestic activity observed in 2021 following the repeal of coronavirus regulations. Downside risks to this outlook include potential climate-related disruptions to the country’s agriculture-dependent economy. The externalities of the Ukraine conflict will also continue to pose a headwind to growth, with possible disruptions to supply-side activity (as a result of higher input costs). The state may also increasingly channel resources from other areas towards managing rising domestic prices. This could see outlays earmarked for investment in productive sectors (in addition to additional borrowing) directed to such interventions.

That said, heightened insecurity will continue to threaten mining operations, while risking possible divestment. Speaking to this, Russian mining firm Nordgold ceased operations at its Taparko mine in Namantenga province (Centre-Nord region) in April after its staff were subject to several attacks. In response, the government announced that it would bolster security for the key sector; however, a gold mine operated by Riverstone Karma SA in the Yatenga province department of Namissiguima (Nord region) was attacked overnight on 08/09 June, resulting in the temporary suspension of operations. Factors that continue to make mining facilities and interests prime targets for Islamist extremist actors include their proximity to the Nigerien and Malian borders (the key operational areas of Burkina Faso’s Islamist militant groups); their associated security resources (which are the primary targets of militant actors); and their hosting of assets that serve as sought-after commodities for extremist groups (particularly explosives). Additional divestment or persistent disruptions to operations within the sector would notably undermine Burkina Faso’s growth prospects.

The establishment of military zones in the Sahel and Est regions may yet yield some degree of improvement in Burkina Faso’s security landscape over the medium-to-longer term. State-aligned military operations to date have been generally constrained due to concerns for the safety of civilians. Accordingly, the relocation of residents will give Burkinabe, G5-Sahel and French Barkhane forces the scope to launch a sustained and intensified offensive campaign against key militant actors such as the al-Qaeda-aligned JNIM movement in the Est and Sahel regions, with the latter also host to the Islamic State-affiliated ISGS group. This approach should be complimented by additional strategies the military has expressed it will pursue, such as tracking down and dismantling revenue-generating operations for extremist groups and disrupting supply networks. Diminishing the capabilities of these two groups in particular would serve as a net positive for the security environments within what have emerged as the country’s most militant-embattled regions (and mitigate spillover into other administrative divisions). The regional nature of these extremist movements suggests that the military will be unable to completely eradicate them. However, dislodging the groups from their primary areas of operation could provide the government the requisite space for greater state and military penetration to facilitate local development and establish more robust security structures. This could also allow the military to direct its attention to other militant-affected regions such as Nord and Centre-Nord. In this respect, the establishment of military zones is likely one of several intensive yet considered interventions the junta is expected to undertake during the country’s transition. Burkina Faso’s operational and security environment – outside of major urban centres such as Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso – will nonetheless continue to be characterised as extreme-risk over at least the near term. This, as any impact of the forthcoming intervention(s) is likely to only be realised in the medium term at the earliest.